To detect climate-driven trends we need to analyse river basins that are relatively undisturbed by human impacts. Recognising this, some countries have declared 'Reference Hydrometric Networks' (RHNs) of locations where river flows are measured, and where human impacts are absent or minimal. However, to date there have been no efforts to integrate these globally. With the ROBIN initiative, we are now advancing a truly worldwide effort to bring together a global RHN.

The vision of ROBIN is that future IPCC assessments will make more confident appraisals of climate-driven global streamflow change, including floods and droughts, than has been possible hitherto, and that this will underpin improved climate adaptation.

ROBIN Objectives

- Establish a new long-term collaboration of international experts which will develop global capacity for establishing and sustaining RHNs

- Share best practice and skills to create the underpinning for a global RHN through common standards, protocols, indicators and data infrastructure

- Establish a freely available RHN dataset and code libraries to underpin new science and advance change detection studies to support international climate policy and adaptation, including future IPCC reports

- To quantify climate-driven trends in key water resources variables on a global scale to showcase the potential of the ROBIN RHN and serve as a benchmark for future hydrological trend assessments

The need for ROBIN: a global Reference Hydrometric Network

Global warming, associated with the burning of fossil fuels, is changing the world’s climate, and with this, it is altering the water cycle. Future climate projections suggest hydrological extremes (floods and droughts) will become more frequent and severe – further heightening the already substantial impacts they cause to lives and livelihoods, as well as infrastructure and economies.

To adapt to future changes in water availability, we need projections of future flood and drought occurrence. Numerical simulation models are used to provide such scenarios, but they are very complex and highly uncertain. To better understand and constrain these model-based projections, we need to quantify emerging trends in the water cycle. This requires long records of past hydrological observations. River flows are especially useful because river flows integrate climate processes over the large areas covered by drainage basins.

Across the world, there have been many studies of long-term trends in river flow. Despite this past research, however, our confidence in observed trends remains very low – even the state‑of-the-art IPCC reports, which have typically been cautious in their reporting of floods and droughts. The key reason is that most rivers are heavily modified by human disturbances (e.g. dams, large removals of water for irrigation, domestic or industrial consumption). These disturbances can obscure the ‘signal’ of climate change – that is, trends in many rivers may bear no relation to global warming and may in fact be opposing the climate trend, due to human modifications such as dam construction.

To detect climate-driven trends we need to analyse river basins that are relatively undisturbed by such human impacts. In order to advance global assessments like the IPCC, an integrated approach would allow global comparison. Members of the ROBIN consortium have previously pioneered a first trans-Atlantic study in this field (e.g. European (Stahl et al., 2010); Transatlantic (Hodgkins et al., 2017)) . With the ROBIN initiative, we are now advancing a truly worldwide effort to bring together a global RHN.

Current status of the ROBIN network

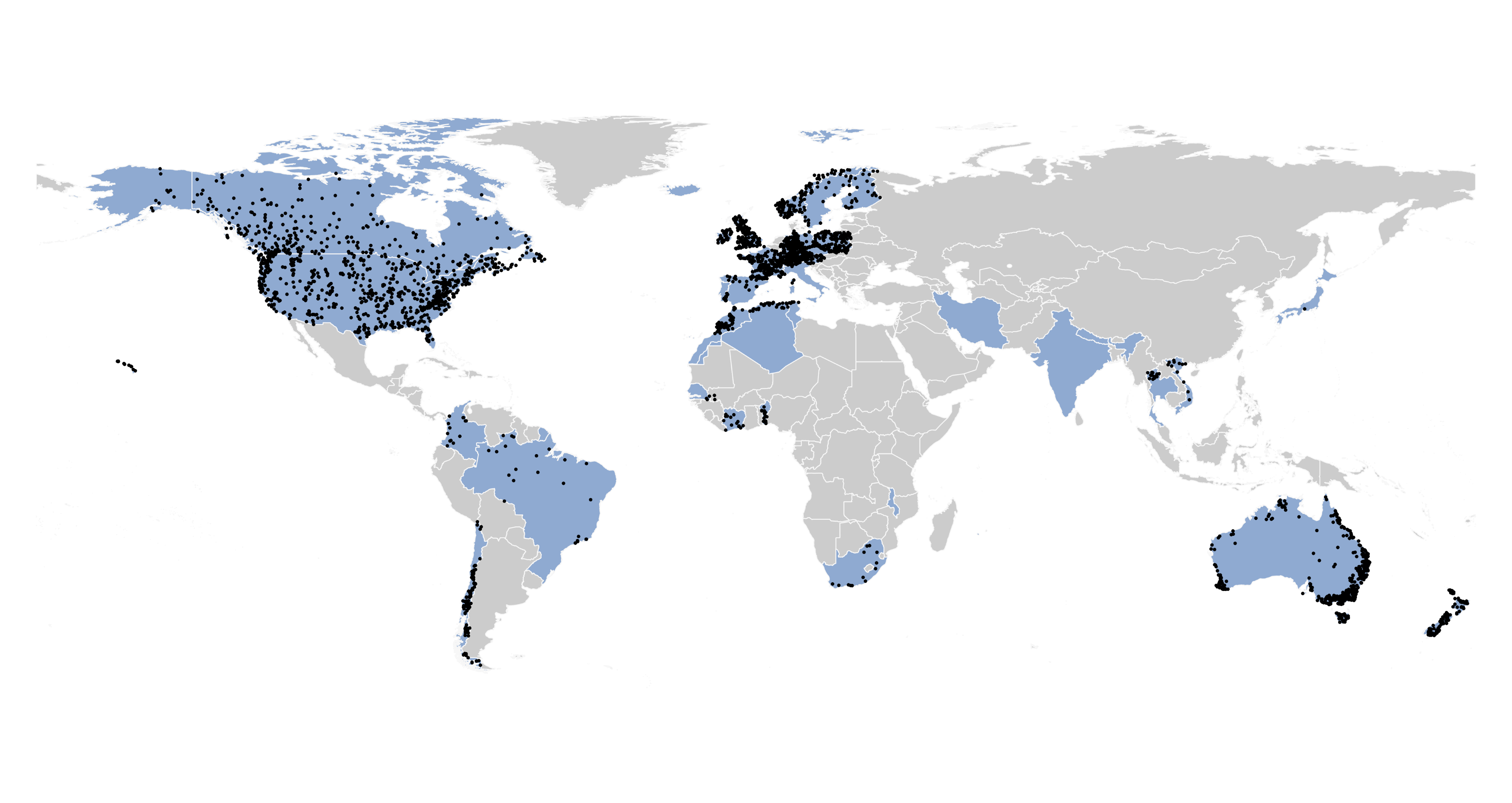

As well as the network of river basins, ROBIN is the network of researchers and institutions sharing expertise. The network includes experts from across the globe with currently in excess of 3,000 gauges. Crucially, these gauges span a broad range of different climates and all our partners also bring specific expertise (for example, unique knowledge of global datasets that can support ROBIN, and specialist analysis of ‘ephemeral’ rivers that often run dry). The below map shows the status of the first version of the ROBIN Network (released in February 2025).

Expanding the ROBIN network

ROBIN will engage other countries to expand the network over the lifetime of the project and set out a pathway to a sustainable legacy for the network going into the future. If you are interested in hearing more about the ROBIN Network, or submitting river flow data from your country please get in touch!

ROBIN outcomes

Crucially, ROBIN is supported by international organisations (UNESCO, WMO and the IPCC) who will ensure sustainability following the two-year project. ROBIN will also deliver the first truly global scale analysis of trends in river flows using undisturbed catchments. This will be a novel, high impact analysis in its own right, but will also showcase the potential of the network. Our criteria for success will be that future IPCC reports will cite ROBIN research and the multiple scientific papers that will be supported by our data legacy.

Partners

| Country | Organisation | Names |

|---|---|---|

| Algeria | University of Annaba | Hamouda Boutaghane |

| Australia | University of Adelaide | Seth Westra |

| Austria | University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna | Gregor Laaha |

| Benin | University of Parakou |

Ernest Amoussou |

| Brazil | National Water and Sanitation Agency | Walszon Lopes |

| Canada | University of Saskatchewan | Paul Whitfield |

| Chile | Center for Climate and Resilience Research | Camila Alvarez-Garreton |

| Columbia |

University Javeriana - Bogota |

Juan Diego Giraldo Osorio |

| Cote d'Ivoire | Université Nangui Abrogoua | Albert Bi Tié Goula |

| Czechia | Czech Hydrometeorological Institute, Czech University of Life Sciences | Jan Daňhelka, Martin Hanel, Yannis Markonis |

| Finland | SYKE - Finnish Environment Institute | Jari Uusikivi |

| France | INRAE - National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food | Benjamin Renard |

| Germany | University of Frieburg | Kerstin Stahl |

| India |

Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee |

Sharad Jain |

| Ireland | Maynooth University | Conor Murphy, Paul O'Connor |

| Japan | University of Tokyo, Meteorology and Hydrology Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute | Yuko Asano, Takanori Shimizu |

| Malawi | University of Malawi | Cosmo Ngondondo |

| Morocco | Cadi Ayyad University | Mohamed Elmehdi Saidi, El Mahdi El Khalki, Rachdane Mariame |

| New Zealand | University of Otago, University of Oxford | Daniel Kingston, Sarah Mager, Sophie Horton |

| Norway | NVE - Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate | Anne Fleig, Anja Iselin Pedersen |

| Poland | Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Gdansk University of Technology | Mikołaj Piniewski, Tomasz Berezowski |

| Portugal | University of Évora | Maria Albuquerque, Nuno De Almeida Ribeiro, Rita Fonseca |

| Senegal | Gaston Berger University | Ansoumana Bodian |

| South Africa | South African Environmental Observation Network, Stellenbosch University | Michele Toucher, Andrew Watson |

| Spain | University of Madrid | Luis Medeiro |

| Sweden | Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute | Berit Arheimer, René Capell |

| Switzerland |

Federal Office for the Environment |

Caroline Kan, Petra Schmocker |

| Thailand | King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi, Chulalongkorn University | Chaiwat Ekkawatpanit, Supattra Vissesri |

| Tunisia | National Engineering School of Tunis | Hamouda Dakhaoui |

| United States |

United States Geological Survey |

Glenn Hodgkins |

| Vietnam | Nong Lam University | Hong Xuan Do |