Saltmarsh degradation results in biodiversity loss and the release of carbon and greenhouse gases stored in the sediment. As the UK aims for net zero by 2050, the restoration of coastal habitats has never been more important. Fortunately there is potential for restoration, with past findings and current research paving the way for habitat protection, carbon storage and adaptation to climate change.

Saltmarsh importance

Saltmarsh habitats make up approximately 36,000 ha of English coastline, 7000 ha of the Welsh coastline, and 6000 ha of Scottish coastline, collectively an area roughly the size of West Yorkshire. Saltmarsh provides habitat for land and marine creatures, nutritious grazing for livestock, and popular spots for fishing and birdwatching. Saltmarshes have featured in popular fiction and folk stories as remote landscapes haunted by dangerous people and strange creatures. The fast incoming tides which for centuries evoked fear of stranding are rising with sea levels, and washing away this intertidal fringe of the UK, of which 85% has been lost since the mid-1800s.

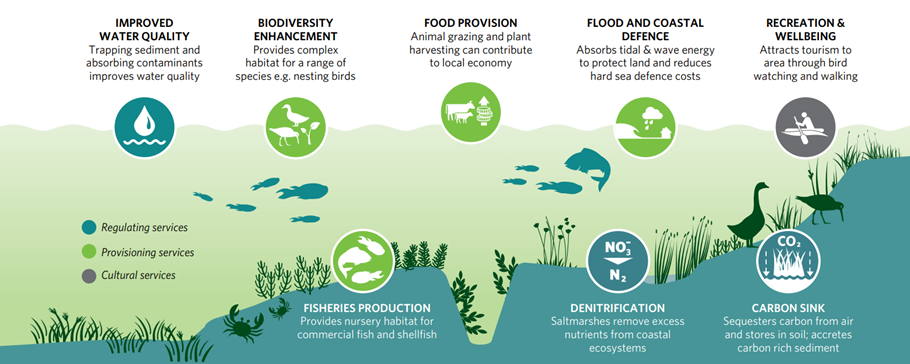

Political and scientific interests focus on issues of land reclamation for agriculture and development, sea level rise, indirect effects of industrial fishing on associated habitats like seagrass and oyster reefs which provide protection from wave erosion, health and well-being benefits, and now carbon sequestration, nutrient remediation and co-restoration of coastal seascapes.

Coastal protection

More than 500,000 homes and businesses in England alone are located in areas at risk of damage from coastal flooding. By the 2080s this could increase to up to 1.5million properties. Damages from coastal flooding and erosion are currently estimated at over £260million on average each year. To avoid this risk getting worse, the Environment Agency has estimated an average spend of over £1billion a year in flood and coastal protection over the next 50 years. Saltmarshes are widely recognised for their contributions towards coastal protection by dampening waves, reducing storm surges, and minimising coastal erosion, encouraging investment in them as a nature-based solution for coastal protection.

Blue carbon

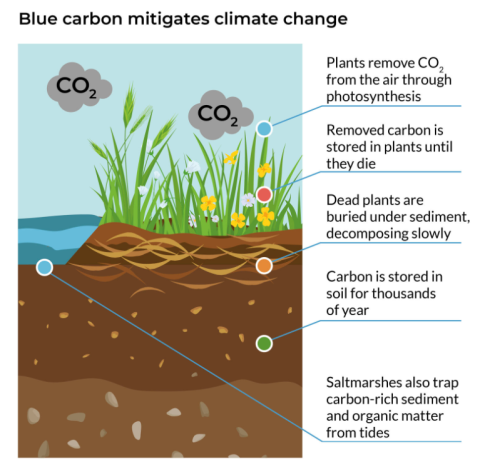

Sediments and organic detritus deposited up the tidal channels and among the roots of saltmarsh plants trap carbon and vertically build up the marsh, giving saltmarshes the title of a ‘blue carbon’ storing habitat. As the UK works towards Net Zero by 2050, carbon storing habitats are becoming increasingly important for offsetting emissions of CO2.

Nutrient Remediation

Saltmarshes, with their daily, seasonal and annual tidal rhythms, are also hotspots of nutrient cycling. The plants and microbes acting in and on the sediment’s stage prevent nutrients, such as nitrate and phosphate, entering the marine environment where they have the potential to create ‘dead zones’. As the UK works towards Nutrient Neutrality it has become ever-more important to quantify the capacity of intact and restored saltmarsh habitats to remediate nutrient pollution while maintaining biodiversity.

Connected habitats, Connected benefits

Habitats do not exist in isolation; there are always connections via flows of water, nutrients, organic matter and even by the movement of mobile animals. Saltmarshes host visitors from land, rivers and sea such as insects, birds and fish. Wrack swept in from seagrass meadows, seaweed forests and the rivers are broken down and buried, building the banks of the marsh. Saltmarshes dampen waves and mop up excess nutrients and sediment which can in turn protect seagrass meadows.

Not only are habitats connected, but the processes and properties in the habitats are connected too. Biodiversity can be changed through additional nutrients, while the biodiversity itself can affect how protected the coast will be, as well as rates of carbon sequestration and nutrient remediation.

Yet, the effects of coastal habitat connectivity and how processes relate to eachother are not yet well documented in a temperate coastal setting. Scoping what is known and where the research gaps remain is a key part of understanding how restoration efforts and habitat loss may impact multiple habitats and how to best carry out seascape-scale restoration.