For 2020 so far, the hydrological situation has been extremely mixed. In February we saw record-breaking rainfall and river flows, and one of the most significant flood events of recent years. Just a couple of months later, after a prolonged period of dry weather, records were broken at the other end of the hydrological spectrum. In the latest in a series of blog posts from our National Hydrological Monitoring Programme, the team considers what has been happening and what may be in store in summer 2020...

In February, several severe storms (including ‘Ciara’ and ‘Dennis’) brought record-breaking rainfall monthly totals for parts of the UK. With this rainfall falling on already saturated ground, river flows responded rapidly and many new February peak flow records were established. As discussed in our briefing note, this caused widespread and sustained flooding in many parts of the country.

An exceptionally dry spring so far?

March is often a 'transitional' spring month but the contrast between the first and second halves of March 2020 was remarkable. It started with the remnants of the stormy February and further unsettled weather continued through to mid-month. Following this, settled conditions under high pressure became established, bringing dry and sunny weather which persisted, in the most part, to the last week of April.

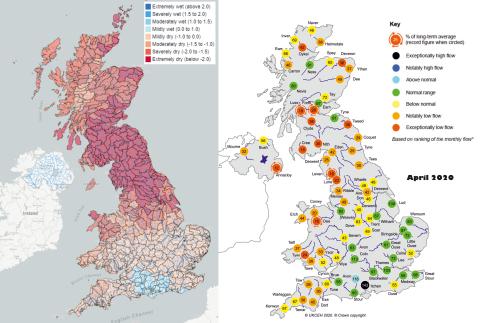

Figure left: Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI) for one month (April 2020) showing extent of dry weather across the UK. From the UK Water Resources Portal. Figure right: April monthly mean river flows for the UK. From the Hydrological Summary for the UK – to be published 15 May 2020.

For April, rainfall for the UK registered at just 41% of the long-term average. Regions receiving even less included Northumbria, which recorded just 8% of the long-term average, making it the driest month the region has seen since records began in 1910. The Standardised Precipitation Index (an index widely used for drought monitoring) for April 2020 (pictured above left) shows large swathes of northern Britain have been extremely dry. There was some rain in the latter part of April, particularly in southern England, but this did little to alleviate the dry conditions that dominated the earlier part of the month, and below average rainfall was recorded in all regions of the UK. Furthermore, despite some localised heavy rainfall, settled and dry weather also dominated through the first two weeks of May.

Latest data from the Hydrological Summary for the UK (to be published on 15 May 2020) show average April river flows (pictured above right). These reflect the prolonged dry weather, particularly so in responsive catchments of northern and western Britain, where a number of catchments registered record low April mean flows (for example, on the Luss, Forth, Cumbrian Leven, Welsh Dee and Annacloy).

For April 2020, rainfall for the UK registered at just 41% of the long-term average. Regions receiving even less included Northumbria, which recorded just 8% of the long-term average...

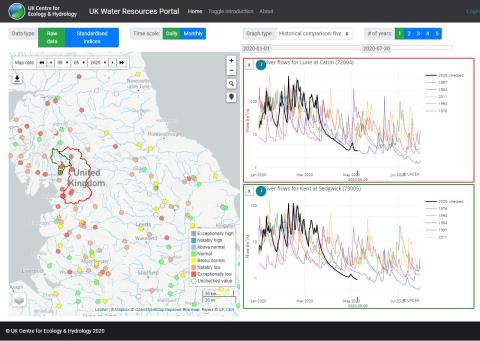

Similarly, the UK Water Resources Portal shows that flows have largely continued to recede into mid-May and, for many catchments, flows are approaching the lowest we’ve previously seen for the time of year. Certainly, in many catchments in Cumbria, flows are lower in mid-May than at the equivalent time in significant drought years like 1984 and 2011. Examples from the Portal (pictured below) illustrate the remarkable transition from some of the highest flows on record in late February to near-seasonal minima in late April/early May.

Figure: Screenshot from the UK Water Resources Portal showing flows on the rivers Lune and Kent in Cumbria are currently lower than in notable drought years like 1984 and 2011.

Are river flows low everywhere?

Not quite! In fact, flows in many permeable catchments in southern England are currently notably high. Sustained by high groundwater levels in these areas following the healthy groundwater recharge season last winter, any recessions have been much slower compared to those in the north-west and flows in many catchments in the south remain above normal or notably high (such as on the Pang, Itchen, Test).

Figure: Recent data from the UK Water Resources Portal (9 May 2020) showing steep recessions over the last two months in the north-west (example of the River Kent in Cumbria), while permeable catchments in central-southern England (such as the River Pang), buoyed by high groundwater levels, remain above normal with much slower recessions.

What can we expect for the rest of spring and summer?

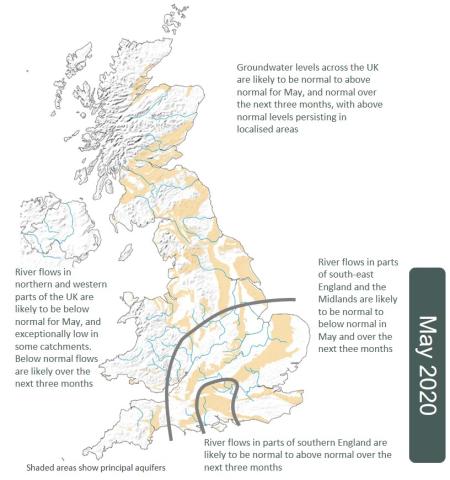

The recent Hydrological Outlook forecasts our hydrological prospects for the next one and three months (May, and May – July). The continuation of below average rainfall is predicted over the next three months, meaning river flows in northern and western parts of the UK are likely to continue to decline and remain below normal in May, with exceptionally low flows likely in many areas. Further south, in the Midlands and south-east England, flows are also likely to be below normal, although not quite to the same extent as further north. In parts of central southern England, flows in some permeable catchments are likely to remain above normal.

Over the three months to July, this contrast between the north-west and the south is likely to continue, although there is less confidence in the longer term projections for responsive catchments in western parts of the UK. While current Outlooks favour a continuation of the present situation, the predictability of rainfall over this timescale in spring/summer is low. And in these responsive catchments, any change to the weather can quickly manifest itself as recoveries in river flow. There is more certainty in the forecast that groundwater-fed rivers in parts of southern England are likely to remain normal to above normal, given how slowly flows evolve in these areas.

Figure: UK Hydrological Outlook for May 2020

Soil moisture deficits will continue to intensify and, with increasing evapotranspiration rates and warmer temperatures as we move into summer, it is likely we will see some agricultural stress – possibly sooner rather than later as soils are already beginning to dry out. Further up-to-date information on soil moisture is available from COSMOS-UK.

Reservoir levels at the end of April were slightly below-average at the national scale. More locally, some individual impoundments in northern England and Scotland were approaching 20% less than the average we’d expect for this time of year.

With current low flows, and if the projected below-normal rainfall over the coming months comes to pass, it is likely we will see some stream network contraction and environmental impacts in rivers (for example, water quality and ecological issues). If rivers in northern and western Britain continue on their current trajectories, there could be pressure on water resources in the summer. Resources in these parts of the country are vulnerable to dry and warm spells in the spring/summer, as in 2011 and 2018. As we all know, however, the weather can change rapidly in northern and western areas of the UK!

With contributions from Lucy Barker, Jamie Hannaford, Bronwyn Matthews, Katie Muchan, Simon Parry and Cath Sefton.